Joel Spolsky stated that as a software engineer one can have a great workspace experience in the software company. When I first read it, I worked for the hardware company, in fact, and it took me a while to understand what he meant. Let’s say he was 50% right.

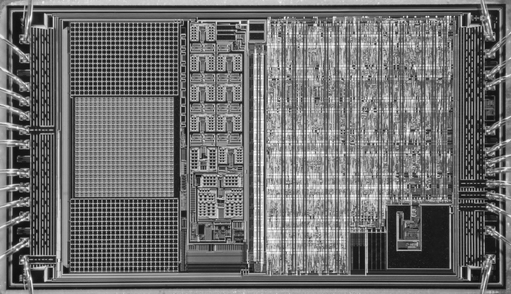

What I share with you here is my experience is backed by one year of internship at Xilinx in 2011, followed by three year full-time 2012–2015. I worked for a hardware/software team writing low-level drivers to the OS used for stress-testing of silicon. Such an OS runs on a silicon prototype, and tries to beat your CPU and I/O subsystem to death. This all is done in hope silicon issues will get exposed before the chip hits the fab, which means huge money savings.

Note: I was very lucky, because I joined an experienced team, and worked with good people. Things like this you can’t really control upfront, and I do agree that your experience may vary, depending on where you go.

Process

Every part of the tool chain in the hardware industry moves slower than in pure software companies. I always give Tcl as an example, which just got included in recent hardware modeling tools. On the contrary, people who will enter workforce this year don’t even know what Tcl is. Other tools have Motif-based UI and look like from previous generation. But since they are mostly solid and stable, there’s no need to rewrite. There’s a space for good software engineers, because semiconductors are transforming. New expectation is that most of the platforms will run OS of some sort. Often Linux. And for this there’s a lot of software to be written on all levels: BootROMs, firmware, loaders, linkers.

You may like it. If you’re like me, you can pick up a technology and just stick to it. The more comfortable you get, the more you forget it’s older and maybe less fleshy, but you can get from A to B as well.

If you wonder where you can find long-lasting software, it might be a hardware industry. Because some of the customers of big semiconductor companies want to have 10–20yr guarantees on the supply of parts, all the tools have to keep backward compatibility. Which leads us to…

Software architecture

As stated earlier, I was lucky: the OS I worked with had an outstanding quality. Much better to what you can get in the Open Source, with coding standards and conventions enforced in a much stricter way. You really sweat during the code review and you can’t use any silly excuses.

To some extend it reminded me working on FreeBSD. The thing you build support N different architectures, and if you want to change a shared piece, it’ll mean a lot of testing.

You’ll get to see some ugly looking code too. Code written by hardware engineers who never done any real software, for example. And you’ll have to live with it. The value of the legacy code is just simply to big to throw some of it away, and rewrite.

This is what I believe was one of the major lessons: incrementally fix and improve, instead of replace. Replacing too often ends up giving you something only 5% better (or worse: 0 or -5% better), with no apparent advantages.

There’ll be a lot of code written 7–10 years ago, and you won’t get a chance to learn why things are done certain way. My belief is that I picked up some code-reading skills too because of that.

Skillset

Unless you’ve worked at the hardware company, you will have a hard time getting your hands busy with real computer engineering. During university I’ve worked with assembly and believed I understood caching effects. Only when you get to solve some real production issues do you get a sense of what’s going on in the computer system. I always say that joining Xilinx was one of the best decisions I’ve made in my life, since being able to reason about software from the lowest-levels is very valuable going forwards with your career.

Things you can expect to learn

- how CPU works

- how CPU and memory busses work

- how switches and intelligent interconnects work

- bringing analog and digital worlds

- clockings and dividers of frequencies

- true full-stack software architecture (how HDL code ties to assembly code, how assembly ties to C and later what the impacts of these relationships can be on the user)

- physical and virtual memory management

The good thing is that unlike schools which often give you a CPU simulator or an abstract, simplified model of the CPU, here you have a real thing, which is destined to hit a shelf and start shipping to the customers. And it’s up to you to debug it, and the firm provides you whatever it takes to narrow down issues.

Equipment

If you like gadgets and big electronic toys, this is the place. Agilent logic analyzers are everywhere, together with multimeters, measurement stations, soldering irons, etc. Labs are filled with top-notch equipment, because during silicon debugging, you need all this stuff. The most interesting toys are definitely full-system simulators, where you can single-step the system on the cycle level. So you can take a snapshot of signals at any clock cycle, look at CPU and memory buses. This is a lot of fun if you’re into systems.

Speed

In my opinion the speed of hardware industry is dictated by cycles. Cycles represent the production of the silicon, and then the deadline of this are near, everything gets very busy.

This is because we’re talking about manufacturing of real physical products, with real tools for real money. You can’t say you’ll be delay, because schedules for the fab, waver testing and finally tapeout are pretty scrictly followed.

Know that semiconductor companies differ. For example, Apple, is is a semiconductor company nota-bene to, is very busy always, since their tape-outs every 6 months are tied to keynotes and new product announcements. Every iPhone, iPad, AirPod and other products have custom silicon.

Methodology

I don’t recall anybody using agile methodology conciously. For sure there were no “sprints”, no “backlogs”, no retrospectives. But there’s a normal division of work: you get a ticket, you estimate it and you work on it. I haven’t found it anymore chaotic than Agile. To be honest, it was more figured out, since the dates and deadlines were known. The chip structure didn’t change, so you know that e.g.: your team will have to deliver five subprojects/pieces of code, and you all concentrate on it.

Money

One of the things which motivated me to move out of the hardware industry was a pay. It’s generally underpaid industry given how much skill and knowledge there is. Unless the connection of the hardware and software is exactly what you want, you may be better of in some IoT startups. You may get a chance to experience similar feel debugging microcontrollers, yet get a decent paycheck.

People

One of the best parts of hardware industry are the people. Because I like to work with people who are smarter than me, hardware environment was perfect. Filled with people who graduated from EE and physics, made me learn thing which otherwise I’d not have known about.

The median age in the semiconductors is higher, so you’ll work with older folks, which is great, since you get to understand the background behind certain technological and strategic decisions. I’ve always had lunch with people with 20+ years of experience of building chips.

Summary

If you’re interesting in a long-term career in computer or software systems, getting your hands dirty with the hardware might be advised. If you start to like and enjoy it, consider doing an internship in one of the semiconductor companies. If you’re naturally drawn to things lying “underneath”, and you’d rather understand the bits and pieces, than to wire big blocks of existing abstractions, the hardware industry may be for you.